Time to Talk About Private Label Wine

Canadian and Australian wine professionals are exercised about the number of wines big retailers currently sell, or may be about to offer, under their own labels.

If you had listened to Chinese visitors at any international trade fair a few years ago, you’d have been sure to hear them ask, almost routinely, ‘Can we have exclusivity? Or OEM?’

When they said OEM*, what they really meant was ‘private label’ - the wine they were tasting, but under their name. Chinese shoppers are notorious for scanning barcodes and checking prices online before making a purchase, so preventing such comparisons can be a key consideration.

As, of course, is the ability for retailers to create their own brands. This explains why, way back in 2017, I was publicly told by an official in Beijing that “Chinese consumers have a million wines to choose from.”

Many of the producers to whom Chinese wine traders put that OEM question responded negatively. Larger ones, however, have often been prepared to discuss the proposal.

Small wineries naturally dislike private labels, if only because of the hassles involved, as do small retailers, which hate seeing private label products on sale at low prices in the large stores with which they struggle to compete.

On the other hand, bigger chains that like dealing with limited numbers of sizeable suppliers, and bargain-seeking consumers, all tend to love them.

Trump-driven private labels

The difference in attitudes to private labels has been highlighted recently by reports that the LCBO, the world’s third biggest booze retailer - after Costco and Total - is considering allowing the sale of private label beer and wine in its territory. This move would be very bad news for smaller Niagara wineries. But it will probably be welcomed by the larger wine producers and breweries that are currently looking for ways to offload their share of US $73m worth of wine that, pre-tariffs, would have gone to the US (out of total exports of $86.6m) and $110m of beer (out of $115m).

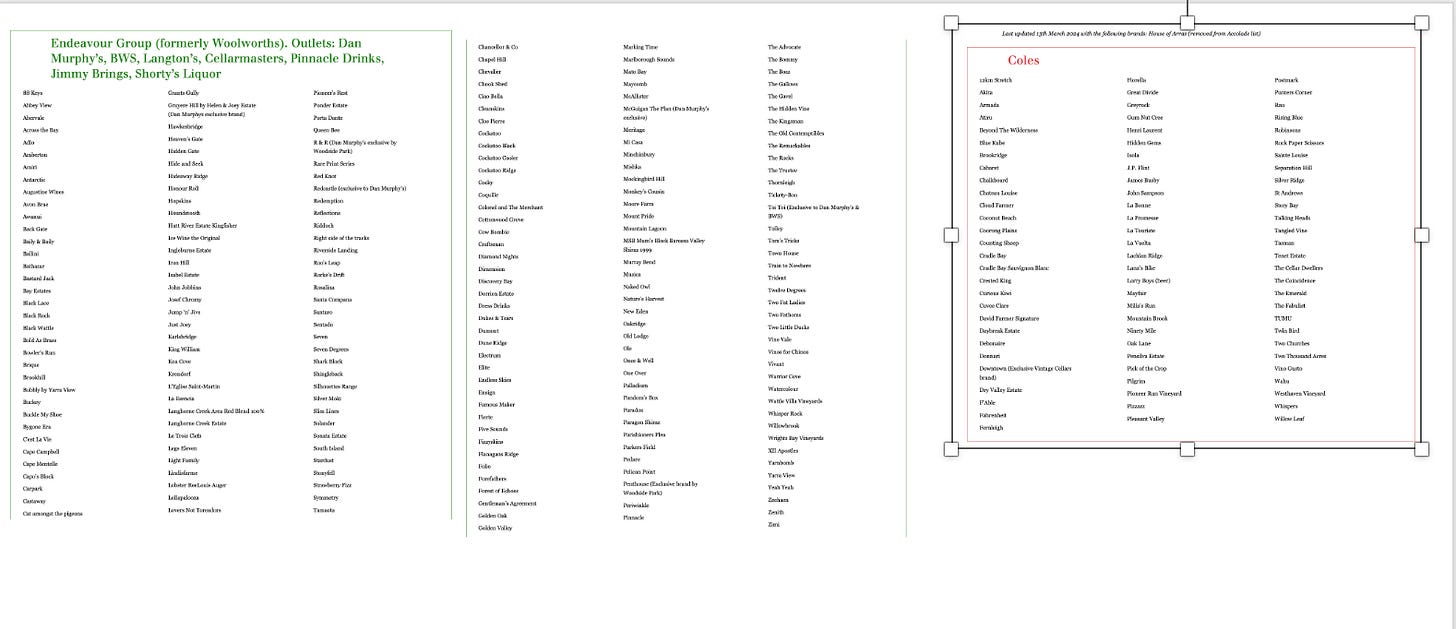

In Australia, private labels are a hot topic among wine lovers, given the level of involvement by the two biggest retailers, Coles and Woolworths. In 2018, it was estimated that one in five bottles of beer, wines and spirits sold by these chains and Aldi were private label; today, the figure is probably significantly higher.

The picture is further complicated by Endeavour Group, the business formed in 2019, from Woolworth’s drinks business, having acquired real wineries and become a producer in its own right. Among those acquisitions, as the Real Review chart below reveals, are once-independent names like Margaret River pioneer, Cape Mentelle; Barossa stalwart Krondorf; and major Australian sparkling wine producer, Minchinbury.

Now, those big retailers have agreed to be more open on back labels about their involvement - a move called for by a Review Of Regulatory Options For The Wine And Grape Sector published by Wine Australia in July.

How much this will change anything remains to be seen.

Bigger than you think

In any case, private label wines are already a far bigger phenomenon than most people acknowledge. By volume, it is estimated that they represent up to 17% of wines sold in the US, and 40-50% in the UK, Germany and the Netherlands. So, for example, a bottle of Champagne could be sold under a retailer’s name, such as Tesco’s Finest Champagne; a brand used by a chain for a range of its ‘own’ stuff: Costco’s Kirkland is a prime example. Or an invented name like Lidl’s Henri Dubois.

Generally wines like these pass unremarked, until a critic or a wine competition compares them to the other, genuinely branded, bottles on the shelf and declares them to be better quality and/or value. At which point, the retailer will probably crow about their success, as Coles, does in this report from the London Wine Competition.

History of private label

Early US retailers were the pioneers of the concept. H. & D.H. Brooks & Co, which became Brooks Bros, is the oldest clothes store in continuous operation in the US. It began to offer its own branded garments in 1818, and Abraham Lincoln, wore one of its frock coats for his second inauguration, and was wearing it when he was assassinated.

After its opening in 1858, the Macy’s department store in New York also introduced its own-label products alongside that other innovation: a fixed-price, no-haggling, cash-only model of selling.

Champagne codes

In Champagne, marque d'acheteur - buyer’s brand - bottles have been identifiable by the letters MA in small print on their labels since the 1940s. When I lived in Burgundy three decades later, negociants commonly had drawers full of alternative names they’d registered (some of which appeared on brass plates next to the front door of their offices).

Today, big suppliers will, voluntarily or not, commonly negotiate deals with supermarkets that combine their branded products and private label.

Kellogg’s cereal packets used to proclaim that “we're so proud of our cereals we don't make them for ANYONE ELSE” and that “If you don’t see Kellogg’s on the box… it isn’t Kellogg’s in the box.”

If you haven’t read those words recently, it’s because of a deal the Corn Flake kings signed with Aldi five years ago.

So, are private labels a bad thing?

I’m afraid that readers who might have hoped I would use this post to demonise private label wines are going to be disappointed.

I struggle to see why wine should not be treated like coffee, tea, beer and everything else in the supermarket.

Like it or not, the wine industry offer consists of tens of thousands of weakly, or frankly not-at-all branded, products that are sold in large retail chains under the name of a region or a grape variety. This is a scenario that might have been expressly created to facilitate private labels.

In Western Europe, around half the wine is still produced by cooperatives that - mostly - lack the skills to launch their own brands. Their business model is based on private label, and that’s not going to change any time soon.

In a world that’s awash with wine (Rioja alone has 150m litres of unsold stock), private label offers a way to deal with the excess that’s better than sending it to be distilled into industrial alcohol

Private labels offer super-premium producers a means of discounting their wine without jeopardising their brand image. This applies as much to the English sparkling wine producers whose wine was sold at a third of its usual price under Aldi’s Bowler and Brolly brand as to the Napa producers behind Trader Joe’s $14.99 Platinum Reserve Yountville Cabernet Sauvignon.

Today, the Chinese wine market is a lot calmer than it used to be, and the chances are that the people raising the subject of OEM/private label are more likely to be producers in regions across the planet, talking to retailers.

This is a very good time to be a professional wine buyer working for a big chain.

* In fact, OEM - ‘original equipment manufacturer’ - is a term that stems from the industrial revolution and more particularly the move by automobile and computer manufacturers to buy components made to their specification from other suppliers. In other words, a pedant would say that an OEM wine ought to be a blend or cuvée that’s exclusive to the retailer. Fat chance!

Apart from writing these posts and working on le Grand Noir and K’AVSHIRI, the two wine brands I helped conceive and co-own, I also offer strategy and marketing consultancy and a range of public speaking.

If you think I can be of help to your business, or would just like to get in touch, please contact me at robertjoseph@winethinker.com

Here in Australia Aldi have a limited range of wines- about the same as what Dan Murphy's have in their fridge section. However each & everyone of Aldi's offerings that I have tasted have been excellent quality at often mind blowing prices. A few years ago Aldi's Blackstone Ridge Margaret River Cabernet at around $20-25 a bottle won the Trophy for the best red wine at the Royal Adelaide Wine Show!!

Exclusive labels and house brands are a screaming deal and IMO often terrific examples of somewhereness, tasty, and generally exceed our expectations! I have consulted on several over the past 30 years both on and off premise. SO IT IS NOT A BAD THING! Cheers. My current favorite is Kirkland Chat. du Pape