Qvevri Confusion - and what it has to do with Wine Industry Woes

Georgia's skin-fermented amber wines are a flea when set against the elephant of the world's wines, but maybe they - and more specifically the way they are received - offer broader lessons

Confusingly, this post both is, and is emphatically not, about Georgia’s qvevri wines. Please bear with me.

Familiar to wine critics and the vinous chatterati across the planet, qvevri amber or ‘orange’ wines, produced by fermenting and macerating white grapes for months in buried clay amphora-like pots, represent a very, very tiny niche. But, in several ways, I see them as emblematic of the wine industry as a whole.

First, the niche: Georgia, where the vast majority are produced, makes less than 1% of the world’s wines. Only 5% of Georgian wines sold in the domestic or export markets are made in qvevris, and some of these are red. So, if all wines were distributed equally across all routes to market, a wine drinker in the UK or US would, by my estimation, have a 1 in 2,000 chance of encountering a qvevri amber wine.

Rare as hen’s teeth

Given the disproportionate presence of these wines in Georgia and a limited number of metropolitan markets, however, the chances of an average, not particularly adventurous, wine drinker who doesn’t frequent Michelin-starry restaurants or hipster wine bars ever hearing about qvevri wines, let alone tasting one are only slightly better than zero.

But what about the people who defy these odds and buy their first bottle or glass? What are they going to experience?

Having just spent two days judging around a hundred amber and red examples at the 2025 Qvevri Competition in the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, I really can’t say for certain.

Multi-coloured

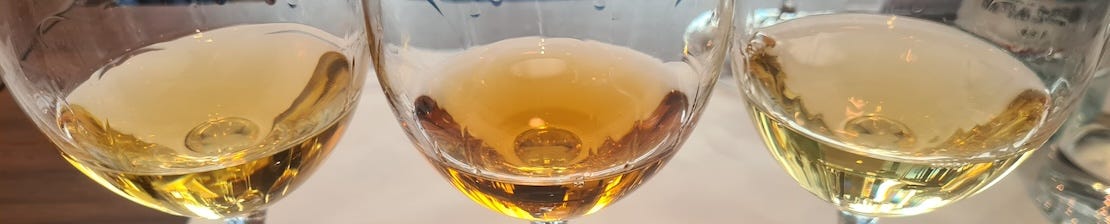

Colours of the supposedly amber wines ranged from maturing Chablis, to deep tawny port. Some had aggressively mouth-drying tannins; others - including ones with what one could call a mid-range hue - might have been readily enjoyed by anyone used to drinking dry white European wine.

Which were ‘typical’? Ah, came the answer from the local experts, that depends. Qvevri wines from Kakheti in the hotter, drier, east of the country, where a few producers still ferment the grapes with at least some stems, tend to be tougher. Those from cooler, damper, Imereti in the west, close to the Black Sea are lighter and softer. The maceration process there is often shorter and some producers don’t use all the skins. As you move up into the hills of Racha and Lechkumi, you can expect the lightest styles of all.

Knowing this kind of thing when buying a qvevri wine, is clearly invaluable to a Georgian, or a British or American somm who has done a lot of homework, but to expect our first-time buyer to recognise any of these names is frankly ludicrous.

Even if they did, though, they’d find the rules are far from absolute. We had soft-tannin examples from Kakheti and the occasional bruiser from the west.

Qvevri wines are often associated with the natural wine movement, but here too, nothing is cut and dried. Few are made from organically certified vines, certification being rare in Georgia; many winemakers use commercial yeasts; fining and or filtering is far from unknown.’Funkiness’ was not a regular feature of the wines in the competition, but we did encounter some occasional mousiness and oxidation.

Artistic freedom

When asked about the diversity of the wines which, for the most part, were good-to-excellent, some of the tasters shrugged and said it was great that winemakers had the freedom to create their own styles, and I found it hard to disagree. But I couldn’t help thinking about that first-timer, and remembering the many conversations I’ve had with people who’ve told me about wines they don’t drink because of the one unhappy experience they’ve had.

Remembering similar confusion over the sweetness of German wines, I wondered aloud whether a simple 1-3 scale could be created that would offer possible buyers guidance to the style of wine they’d be getting. Wines would be tasted and given their ‘tannic-index’ rating by local experts, and use of the scale would be entirely voluntary. Wine critics would be encouraged to talk about the scale in their pieces about Georgia, and restaurants would hopefully offer customers flights of qvevri wines of varying styles.

While there were one or two thoughtful nods, these ideas were not generally well-received. Wine drinkers, it was implied, should educate themselves about Georgia’s regional winemaking differences and/or restrict their wine buying to situations in which there’s a well-informed sommelier at hand. In other words, qvevris are not, and are not intended to be, for the average wine drinker.

Build brands

There is, of course, an alternative partial solution to qvevri-confusion: the creation of strong brands with identifiable styles. Gravner and Radikon are - within parts of the wine community - well-known examples of similar styles from outside Georgia, though I suspect that many fans of either would bristle at my calling them ‘branded wines’.

I’d love Gogi Dakishvili’s Orgo - one of my favourite accessible Kakheti qvevri wines - to become at least as (relatively) well known as those Slovenians, but production volumes of this or most other Georgian amber wines are far too limited for this to be realistic.

Beyond qvevri

Now, as I said at the beginning, I’ve chosen qvevri wines as an example of the wider wine scene. To the delight of wine writers, increasingly wide variations can be found in bottles labeled as Chardonnay, Rioja, Merlot or almost any grape or regional style.

This is far less welcome among the mass of casual wine drinkers. A person used to enjoying Villa Maria or Brancott Sauvignon Blanc might not be pleasantly surprised to encounter the ‘struck match’ reduction character of Dog Point, for example.

Is it surprising then when, faced with a choice between potentially relatively costly bottles, shoppers play safe and opt for the brand they know, or one associated with a celebrity they trust? Or that wine distributors, retailers and on trade outlets are reducing their wine ranges?

The only ways I can think of that will address this situation, are

To provide more information on the label (possibly, but not ideally, via a QR code)

To introduce more smaller formats to reduce the risk to first-time buyers

To focus on offering sampling opportunities in on- and off-premises and - using pouches and tubes - to those buying wine online.

Will any of these stop qvevri wines being a niche style? I very much doubt it, but they just might help to slow the decline in consumption globally, and even in Georgia itself.

At first glance, the ‘cradle of wine’ with its 8,000 years of vinous history seems to be one of the places where wine is most solidly implanted in the national culture and psyche. But earlier this year, the Georgian business publication BTUAI predicted that the domestic market would shrink by 4.2% over the next year.

Maybe, incredible as it may seem, some young Georgians suffer from qvevri confusion too.

I believe that your POV is right on. Wines Orange may even be one of the many many reasons zillenials think they don't like wine as much as cocktails and beers. Cheers!

Orange wines can be considered a brand, wine drinkers they may have never tasted, but they are aware of them. I wrote on the subject long time ago, https://www.italyabroad.com/wine_blog/orange-wines, and the first orange wines I came across were undrinkable, still were selling, wine drinkers were and still are prepared to pay more for an orange than a red wine, let alone white.

You could say that orange wine is a brand/category that so far has not been flooded with cheap wines. Whether the wine is good or not, and there are still plenty of bad, wine drinkers are being charged good money, so I disagree with your statement about price.

The problem with the orange wine brand is that currently people associate orange wine to a natural wine, possibly organic, maybe biodynamic but just an orange wine and there are hundreds of orange wines made with the more disparate grapes, the category is lacking some sort of universally accepted definition and this is very confusing with consumers and if we were to uses a QR code as a possible solution, shopping for a bottle of wine could take hours and consumers would give up on the second bottle.

How do you get people choosing a bottle of orange wine over a bottle of pinot grigio? I dont think you can, however, one thing we can do is to educate wine drinkers but we cannot expect they all be queuing to buy it. First problem with orange wines, something even most sommeliers are not aware of, is that they should not be served like white or rose wines, especially the ones with long maceration. People will only buy an orange wine after they have done a bit of research or tasted one and for a special occasion, they will still be buying a non orange wine for any other occasion, so i believe the only way to get people buying their orange is by providing tasting or sampling on the premises where an introduction can be given.