Is Every Wine a Brand? And Does it Matter?

The concept of wine brands is viewed very differently on both sides of the Atlantic. But it can divide Britons too.

Lulie Halstead, founder and former chief executive of the Wine Intelligence agency (among a long list of other senior roles), is one of the professionals I most respect when it comes to data and marketing. We worked together as lecturers on these topics at the WSET business bootcamp, and she has generously shared many thoughts and insights with me over the years. For all these reasons and more, I hesitate to disagree with her.

But, I beg to do so over her recent assertion on LinkedIn that

“Every wine is a brand, whether it’s treated, managed, and understood as one or not. Some wines are strong, resonant brands; others are weak or neglected ones. Calling them ‘labels’ is really just shorthand for thin brand equity. But consumers still form associations the moment they see the name or the bottle — and those associations, however faint, are the brand. The real question isn’t if a wine is a brand. It’s whether the business is investing to make that brand meaningful and valuable.”

The reference to ‘labels’ refers to a belief I had shared online that this, or ‘wannabe brands’, is the more accurate way to describe most of the world’s wines.

On your marques

Talking about brands in the context of wine is often contentious, especially in France, where the French word ‘marque’ is acceptable when talking about ‘Les Grandes Marques de Champagne’, but not for Bordeaux chateaux or Burgundy domaines. The French-language Wikipedia revealingly describes a ‘vin de marque’ - branded wine’ - as one that has been ‘elaboré - ‘put together’ - bottled and distributed by a négociant.

I’m not presenting Wikipedia - in any language - as being a hundred percent accurate, but decades of discussions in France leave me with a clear impression that, apart from Champagne with its long history of marketing, ‘branded’ wines are associated with mass production that also - with a nod back to the days following phylloxera - might well have involved adulteration.

In any case, ludicrously, by the Wikipedia definition, Whispering Angel is not a wine brand.

What is it?

Before going further, I guess we need to agree on what a ‘brand’ really is in the broader context. The origins of the Anglo-Saxon word go back to the way American cattle ranchers used to identify their animals to protect them from confusion with their neighbours’ beasts, and more importantly, from poachers. This explains the modern definition of ‘name given to a product or service from a specific source.’

There are other ways to define ‘brand’. I like the advertising guru, David Ogilvy’s “the intangible sum of a product’s attributes.” But I prefer another adman, Sir John Hegarty’s, more recent “the most valuable real estate in the world: a corner of someone’s mind.”

My own humble offering takes the form of a negative: a brand is the opposite of a generic product or commodity. Lavazza, Starbucks or Nescafe, rather than ‘coffee’. Uber, not ‘taxi’. Pink Lady apples.

I find this works across a broad range of sectors, from treating a headache with Nurofen or Tylenol, to Googling on your iPhone.

In all of these cases, there’s a generic alternative, though I admit that I can’t recall anyone using the words ‘search engine’ in casual conversation.

Four star generics

When we look at wine, though, generic all too often rules the day, from ‘glass of white’ or ‘fizz’, to Chablis and Chardonnay. Halstead agrees with me in believing that “Beyond commodity products, everything we buy is a brand.” In my view, however, if people treat something as a commodity, it doesn’t qualify as a brand - for them, at least.

Of course, enthusiasts pay attention to the name of the producer - though not always carefully enough to name it the next day - but casual drinkers rarely trouble to register it, unless it forms a major part of a memorable label. This is usually the case with New World varietals, but far less often with traditional European PDOs. With a few exceptions, such as Campo Viejo Rioja, Mouton Cadet Bordeaux and, of course, Whispering Angel Provence, the brand that acquires the cerebral real estate is the word printed in the largest font: the appellation.

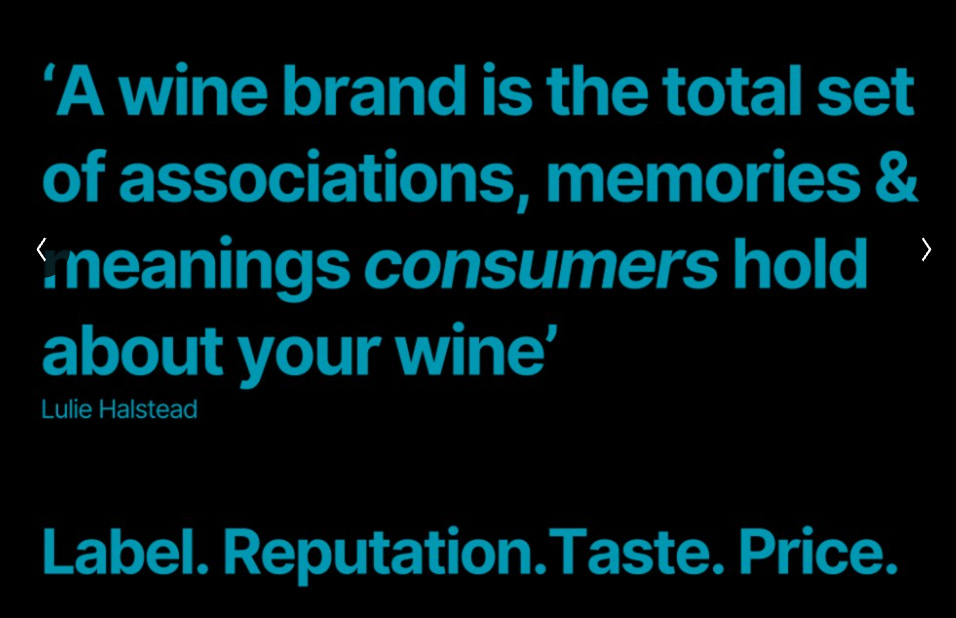

As Halstead says, echoing Hegarty, “A wine brand is the meaning in the consumer’s head.” And as I would reply, most producers’ names and identities never penetrate those heads sufficiently to have any ‘meaning’.

Hitting the target

Now, to be fair, like ultra-pricy watches and hi-fi equipment, there are Chablis and Châteauneuf du Pape producers whose names are sufficiently familiar to their target customers to be called brands even if almost nobody else has ever heard of them.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Wine Thinking to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.